“My obsession is just with like, the mechanics of the earth,” the artist Ryan James MacFarland told me recently, standing in his apartment with test prints laid out all around us. “I’m obsessed with natural phenomena, like with the moon during the day pictures, I did seventeen of those in five years.”

It’s these natural moments that seem counter to time and space that Ryan enjoys most in his photography. Zooming in on a daytime moon, or a patch of forest on the side of a mountain, or a few waves in a giant lake, he deducts gravity, time and space leaving the observer grasping for a way to understand what it is they are viewing. “My photos are landscape photography without a horizon line.”

“I really like the fog,” he says, of his dozen fog prints. “How fog moves, it’s just too cool to believe.”

Adding: “The biggest inspiration in the last three years – which has been totally unconscious and I didn’t do it on purpose – has been all of David Attenborough’s documentaries because Dave watches them to go to sleep every single night. It’s also weird because they’re on while I fall asleep so I feel like it’s subconscious.”

Ryan’s partner David Harper is the curator of BAMarts at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and full disclosure, he and I went to punk shows together a lot in our younger days. David’s many curation projects in New York and beyond also connected the talented duo to the brand new Shandaken Project in upstate New York where artists and writers can go to disconnect during summer residencies. Ryan spent a month there in 2012 after opening a solo show in July called Tide Study that included his natural images at Charles Bank Gallery.

About two hours north of New York City, “The Shandaken Project supports experimentation by emerging and mid-career artists, writers and thinkers, and curators and other producers of culture with free residencies that include room, board, and studio space.”

For a small group of artists – only three live here at a time – working in the high paced, high stress environment that is the New York art world, the sustainable studios dotting the perimeter of the Saltbox-style house hope to be high-impact respites. Surrounded by national forest, the 250-acre property has stunning views and a spring-fed lake. The main house with four bedrooms and limited internet access, but a plethora of manual tools, sits on the plateau of the mountain. An arts supplier and hardware store are about 15 minutes away by car.

“In the wake of 2008, younger and mid-career artists took heavy blows from a financial meltdown that stripped them of one support system after another. And as the art industry becomes increasingly professionalized and cities, particularly New York City, become more restrictive and gentrified, it becomes harder for artists generally to avoid colluding with the marketplace.

We believe that 2008 was an object lesson about the unsustainability of top-down funding models, and that in coming years, capital will assert itself with increasing ferocity in the field of ideas. The Shandaken Project exists to address these problems: by focusing on community development and support, and creating a space where experimentation, process, and research are privileged as ends in and of themselves.”

“The property on which Shandaken Project residencies take place is nestled on a completely private mountaintop, with an intentional focus on an individual experience of place,” the founder Nick Weist wrote to me over email.

Nick, formerly the Marketing Director of Creative Time, spent time upstate on a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) farm, and incorporated maintenance and growth of a large edible garden into the project. Every resident – only three live there at a time along with Nick – must spend 3-10 hours in the garden per week tending and harvesting their own delicious fresh produce while reconnecting with each other and the land.

“As such, while there, the residents and I are empowered to easily disconnect from major media outlets: in my case for four months and for the residents up to six weeks at a time,” he wrote.

During Ryan’s time at Shandaken he cleansed his palate after putting together a big show, hiked and allowed himself the space to explore and play with the mechanics of nature and the line between natural and synthetic.

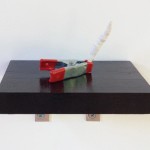

While there he whittled a dead tree into a striking white forest sculpture, created stalactites with synthetic materials and honed in more on his performative skills. All examples of work that existed outside of the marketplace, but whose process is meant to lay the foundation for work still to come. For Ryan that’s preparation for a solo show this spring.

“I did this performance when I was up there,” he started to tell me, smoking a cigarette on his balcony overlooking a maze of Williamsburg buildings old and new.

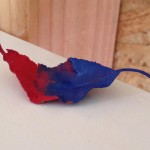

“There was a big party for all the people who donated to the Kickstarter to build the studios. It was the day after the opening day of the Olympics and since I knew we didn’t get to see it, I was determined to put on my own opening ceremony at Shandaken. So I built an Olympic torch – it was a beer-amid – I insisted on the fact that I had to drink every beer to make it. So I had to drink 88 beers. Minimum 8 beers a day for like 14, 15 days.”

And how was this all received by the supportive Kickstarting crew?

“Ryan’s performative piece was a moving reminder that a small community of people, if it’s lucky enough to include a talented, motivated artist like him, can mark world events without relying on corporations to guide our experience,” Nick told me. “I’ve never partaken in a more fun or satisfying celebration of the Olympic spirit, which in this case was distilled into a floating, flaming tower of red, white, and blue beer cans.”

Later, someone compared the performance, which included smoke bombs, to a Richard Prince-like show of patriotism.

“I don’t know,” Ryan responded, “I just really like America. Maybe growing up in the South had a lot to do with it. There are a billion things I can do here that I would not be allowed to do anywhere else.”

His next show, sometime this spring, might delve into that concept or not, but ultimately, Shandaken’s success was similar. “It’s nice to go away,” Ryan continued, as I was getting ready to leave his lovely loft.

“I didn’t even think about, ‘I wonder if someone commented on a photo of mine today?’ It just never crosses your mind, which is awesome because I’m probably thinking about that way to often or more than I’d like to.”

Be First to Comment