“I always think of Fletch, the movie from the 80s with Chevy Chase,” one of the FAILE Patricks, distinguished as Miller, said at Lincoln Center last week, “and how easy it is if you just sort of go that little extra distance and put on the costume and talk the part. A lot of people just accept you as how it should look.”

Along with the graffiti artist taeOne, the three of us were standing around one of the world’s grandest cultural jewels talking about the best strategy for illegally vandalizing things in New York City. At the New York City Ballet, inside of a building named for the reprehensible industrialist David Koch.

“One thing we learned is doing it during the day is a much better idea,” Patrick told us. “That alone has been a much better plan.”

“What is the advantage?” asked taeOne.

“It just looks like you’re supposed to be doing it,” Patrick answered. “It looks a hell of a lot better to the cops.”

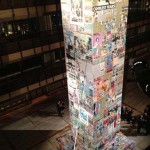

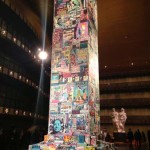

There are at least some parts of town where that is true – and they were nowhere near where we were standing, under the forty-foot tall ceiling of this luscious alter to New York’s cultural dominance. It was a world away from where the FAILE tower, open to the public through February 17 and installed through the spring, was first conceived.

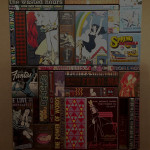

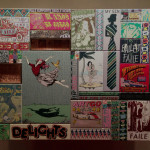

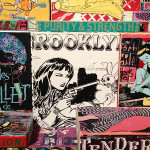

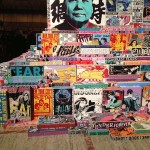

“We’ve always been working in the studio while working in the street,” he continued later. “The first apple box we ever found was in the street – it was leftover from a film set, they forgot it or something – in Williamsburg. We said, ‘Shit, this is a really beautiful box’ and we brought it into the studio and painted it and printed it and started just stacking them – small stacks and big stacks – and eventually that led to this. You find a lot of things just stumbling across the landscape.”

Is it totally serendipitous? I asked. “Totally serendipitous.”

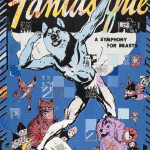

In fact many rising artists have taken to Brooklyn’s streets over the last decade and a half, as FAILE has, to proclaim their messages through various forms of what the NYPD calls vandalism. Wheat pasting, painting, spray-painting, stenciling, are all acceptable mediums of street art – now this so-called vandalism has the potential to propel international art careers.

“It’s just a vehicle for the work,” Patrick Miller said of working in the street. “I hate it when people pigeonhole street art and graffiti as specific things because a lot of these artists are great artists, it’s just a medium they choose to work in – that doesn’t mean they’re not artists.”

He may have been referring to the attitude that much of the New York art work has had towards the nascent, but now booming, street art style, which was recognized and promoted in the mainstream art world only outside of New York until the last few years.

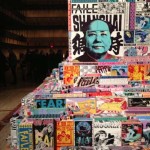

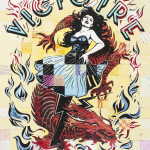

FAILE’s ultimate success in New York sprung from being featured in both a Banksy show – Cans, held in a train tunnel – and a week later, at the Tate Modern. In London. That catapulted the duo through the cultural hoops over the ensuing four years to collaboration with the ballet in New York, as unexpected as it may be. It’s as if they’ve made a career oscillating between the high and low, enabling an average amount of street and fine art world credibility: a difficult feat for rising stars in the digital age.

“I feel good about it,” Patrick said of the collaboration. “I think for [the ballet], here was an institution built on the modern, cutting edge – really pushing it, being very much about incorporating fine art and contemporary musicians at the time, pretty cutting edge.

“Balanchine was like kind of a revolutionary in that sense and that spirit we can all relate to. While at first, when the project started, it was, like, very small and not that interesting, and we [told the ballet], ‘Eh we don’t think it’s such a good thing, why don’t you let us pitch something back.’ And we had wanted to do sort of this monument valley tower kind of idea and there are not very many spaces with forty-foot ceilings and you can walk around the rings.”

And voila, collaboration was born. A performance of the ballet on May 29 will include a small FAILE box as a gift with the purchase of a $29 ticket, collectible bait for the Brooklyn set so desired by traditional cultural institutions such as this. “With the New York City Ballet Art Series,” says the press release, “the Company plans to engage with a new generation of visual artists and audiences.”

Isamu Noguchi, Julian Schnabel, Francesco Clemente, Helen Frankenthaler, Roy Lichtenstein, Keith Haring, Santiago Calatrava, Per Kirkeby, and others, have created artworks and other visual elements for NYCB performances in the past. In the permanent art collection are Jasper Johns’ Numbers, Lee Bontecou’s Untitled Relief, and Elie Nadelman’s Two Female Nudes and Two Circus Women.

Worlds away from such recognized modernists, in the chaotic landscape of street art, timelines and structure are still key.

“If you don’t have a timeline it’s really hard to work in a lot of ways,” Patrick told us as we were wrapping up. “Like downstairs [on the mezzanine] we couldn’t hang the paintings, so we had to make stands for them to be on, and all of a sudden it was like, ‘Wow this totally looks like much more sculptural paintings, we can put them back to back or anywhere’ so all those things led to that.

In fact, pointing to the tower surrounded by gawking press, he added, “This originally came from a column in a gallery space, and we were like, ‘What the hell are we going to do with this column? Its terribly ugly’ and we were like, ‘Let’s make a tower out of it. A short tower.’”

[…] the majority of my evening last Monday surveying the crowd at Lincoln Center’s preview of Les Ballets de FAILE for anyone who looked like a possible graffiti […]